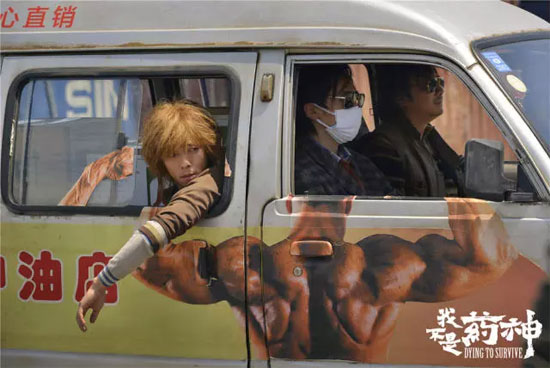

Film Name:我不是藥神 / Dying to Survive / Drug Dealer

Feeling overwhelmed by all the buzz? You should be. After watching the film, I’m even more convinced of this.

Without a doubt, “Dying to Survive” is destined to become the biggest phenomenon among domestic films this July—and perhaps even this entire year. Beyond its commendable quality, its status as a “realistic drama” has cast an indestructible aura of power around it. It’s a blessing for all of us to have a film that compels audiences to “focus on those around them.”

Articles about this film are already everywhere. I won’t dwell on topics we’ve discussed repeatedly—like its real-life inspiration, the drugs involved, or the social phenomena it highlights. Instead, I’ll focus solely on the film itself.

[Friendly reminder: Spoilers ahead.]

What truly astonished me while watching the film wasn’t the grim reality it portrayed (after all, I was already familiar with much of it before its release), but rather the film’s own level of polish and expressive power. It’s safe to say that even if you stripped away the immense energy derived from its subject matter and replaced it with a more mundane story—something like “I’m Not a Door God,” “I’m Not a Car God,” or “I’m Not a Charlatan”—it would still stand as a rare gem of a film.

Its most striking feature is its seamless flow from beginning to end—a truly cohesive and satisfying viewing experience.

The story isn’t complicated—it’s about smuggling banned drugs for profit until one’s conscience kicks in. But conveying it clearly and portraying it with depth is far from simple.

Within just half an hour, “Dying to Survive” utterly stunned me: Cheng Yong’s wretched existence, the desperate plight of leukemia patients like Lü Shiyou, and the crushing reality of exorbitantly priced genuine drugs—these intertwined forces propel the characters into the perilous act of drug trafficking. The entire process unfolds with remarkable clarity and completeness, balancing grand scenes with intimate details. Every necessary shot is present, yet all are executed with restraint, never dragging on. The editing and pacing are remarkably crisp and efficient.

This is director Wen Muxian’s debut feature film. Even if he may have received guidance from “seniors,” this level of “maturity” remains remarkably impressive.

Patients wanted affordable life-saving drugs, Cheng Yong wanted to make big money—and so this “promising business venture” was sealed.

Cheng Yong had smuggling connections and access to supply channels, while Lü Shouyi possessed market acumen and a client base. Together, they formed the initial core. To expand their market reach, they recruited Liu Sihui, who held more patient resources. To grow and strengthen their operation, they later brought in “translator” Pastor Liu and “laborer” Peng Hao.

Thus, this haphazardly assembled ragtag crew launched their “entrepreneurial legend” in the black market for drugs.

Before this, each member of the small team had been struggling… But as the saying goes, “Money gives courage to the timid.” After earning their first fortune, the “Miracle Oil” crew immediately upgraded their tools and lifestyle—a transformation so profound it could be called a complete metamorphosis.

Those accustomed to poverty inevitably swell with newfound wealth. Scenes like Cheng Yong throwing money at the manager to dance during their celebratory drinking session, followed by his persistent advances into Liu Sihui’s room, push this insatiable greed and dreamlike euphoria of sudden riches to a climax.

Beyond its unambiguous narrative, the film shines with numerous ingeniously crafted details—one scene that left a deep impression on me was when Liu Sihui poured water for Cheng Yong and asked him to wait a moment.

Both men were certain of the relationship about to unfold. Cheng Yong basked in the satisfaction of holding all the power, only to have his mouth scalded by a mouthful of hot water… Then the appearance of Huihui’s daughter sent a chill through his heart… A metaphor coupled with a literal image gradually sobered Cheng Yong, whose mind had been clouded by lust. “None of us are anything special—we’re just finding joy in hardship,” he realized. It was undeniably a thoughtful design (other details like Cheng Yong feeding his father, his attitude toward his son going abroad, and Lü Shouyi’s oranges were also rich with meaning).

True to form, the film’s tone and atmosphere undergo a subtle yet palpable shift from this point onward.

The significance of Lü Shouyi inviting Cheng Yong to their family dinner is self-evident. Prior to this, their relationship seemed purely transactional—business partners. Yet the young couple’s words and actions made Cheng Yong feel not just a boss, but a friend and benefactor.

The dramatic conflicts arising from subsequent events unfolded logically thereafter.

“Dying to Survive” possesses a remarkably natural narrative arc, with its cinematic language handled with seasoned skill—laying the most solid foundation for the film’s excellence. This isn’t to say it’s flawless, but compared to its overall quality, any shortcomings are negligible—especially when bolstered by the actors’ outstanding performances.

With this foundation, the film’s thematic exploration flows effortlessly.

In my view, every character in “Dying to Survive” acts without moral fault—even the most flawed individuals possess redeeming qualities.

Lu Shouyi, Liu Sihui, the pastor, and many other leukemia patients traded cheap smuggled drugs to save lives and cling to survival—their desire to live is undeniably justified;

Cheng Yong’s decision to break the law to stand tall and regain dignity is understandable, and his subsequent fear of exposure driving him to cut ties was equally justified. Saving others wasn’t his obligation, especially when it meant risking arrest and imprisonment;

The police chief acted justly in enforcing the law. “The law takes precedence over sentiment” is the foundation of their profession; rules are rules.

“Yellow Hair” Peng Hao’s sacrifice to save Cheng Yong was foolish, yet no one can say he was wrong. It was his last remaining conviction and sense of righteousness.

Cao Bin’s enforcement philosophy of “tightening first, then loosening” is equally sound. When legal principles and compassion left him torn, stepping back was his most reluctant yet appropriate choice.

Zhang Changlin’s long-term peddling of counterfeit drugs is undeniably unforgivable. Yet while profiting from illicit gains, he inadvertently saved some patients. Even after mocking Cheng Yong with the line “poverty-related illnesses have no cure,” he still refused to betray Cheng Yong. Helping someone he disapproved of continue doing what he deemed foolish—who could bring themselves to condemn him?

Even the Swiss pharmaceutical representatives portrayed as the film’s primary antagonists have their own hardships. Major pharmaceutical giants invest immense resources in developing new drugs. Selling medications at premium prices and cracking down on cheap generic alternatives are simply following the “rules of the game”—reasonable and justified. What wrong is there?

Yet when all these seemingly “blameless” individuals and actions converge, the resulting outcome is undeniably wrong.

This unbearable “global tragedy” represents the deepest pain exposed by Dying to Survive.

The film’s success owes much to its artistic quality, but ultimately, it triumphs through its subject matter.

Most domestic films that have achieved both box office and critical success in recent years either cling to “fantasy” for mere amusement or fixate on emperors, generals, heroes, and beauties… If cinema is a “dream machine,” then these films represent either “sweet dreams” that empty the mind of troubles or “enchanted dreams” that loom high above, demanding awe.

Yet the “dreams of reality” that demand we look around us—or even downward—remain underrepresented. These dreams are too real, too painful.

The reception “Dying to Survive” receives today reflects just how hungry audiences are for realistic storytelling.

It’s not that no one is making such films—but constrained by creative limitations, censorship, and other factors, the vast majority of these works rarely find favor with the “market.”

Here, we must admire the perseverance of producers Ning Hao and Xu Zheng: over the years, they’ve never abandoned their exploration of realistic storytelling. Ning Hao’s “No Man’s Land” endured nearly five years of revisions and censorship before finally hitting theaters, and the subsequent success of “Breakup Buddies” felt like a small but significant breakthrough after years of preparation. As for Xu Zheng, setting aside his earlier work, just look at his three films this year (discovering and promoting promising new directors): “A or B” was neither here nor there, “How Long Will I Love U” achieved modest success, and “Dying to Survive” earned tremendous acclaim.

While some still lament the “censorship system,” others have quietly erected a milestone through universally beloved storytelling.

In fact, the film faced considerable pressure to secure a smooth theatrical release. For instance, its title was changed from the originally ironic “Chinese Drug God” (“Indian Drug God,” etc.) to the more straightforward and low-key “Dying to Survive.” Earlier promotional efforts were also kept very low-key, for fear of being misinterpreted or twisted… Fortunately, all the visible and invisible difficulties were overcome one by one.

As a final aside, the film’s release also reflects the nation’s confidence in its healthcare reforms. Whether acknowledged or not, cinema inherently possesses a “propaganda” function. In recent years, countless positive news reports have urged public attention to medical and pharmaceutical reforms and vulnerable groups, yet none proved as effective as this widely acclaimed film.

The success of “Dying to Survive” is, in a way, an inevitability born of chance.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Dying to Survive 我不是藥神 2018 Film Review: The Significant Gap in Realistic-Themed Films