Film Name:無雙 / Project Gutenberg / Mo seung

The National Day holiday box office season is drawing to a close, and it’s now clear: “Project Gutenberg” has emerged victorious.

Riding on its stellar reputation, “Project Gutenberg” defied early skepticism to break through the competition, securing both the highest box office and critical acclaim during the holiday season. This triumph is a victory for quality and a triumph for defying labels—Hong Kong cinema never died. With this work, Andrew Lau demonstrates that whether a film is well-made has nothing to do with the labels attached to it.

You’ve likely heard plenty about Project Gutenberg’s merits—but it wasn’t until the final scene that my lingering doubts dissolved completely, leaving me convinced this film is truly exceptional.

[Friendly reminder: Since it’s hard to discuss this film without spoilers, those who haven’t seen it yet are advised not to read further. Spoilers ahead!]

Project Gutenberg has many merits, but I believe the true catalyst for the film’s current acclaim lies in the successive twists that unfold at its conclusion.

Let me get straight to the point: the film’s true climactic twist isn’t that Li Wen is the painter (a trope used in many films, with this one bearing a striking resemblance to The Usual Suspects). Rather, it’s when all is said and done, Ruan Wen declares he never knew Li Wen at all.

Once you know the ending and revisit the film, you’ll find your appreciation for it deepens significantly.

Below, I’ll revisit the film with this new understanding and also discuss other strengths of “Project Gutenberg.”

The film opens with artist Li Wen being brought back to Hong Kong for interrogation. He is the sole survivor of the “Painter” counterfeit currency crime syndicate and the police’s only lead to track down the “Painter.”

Cowed and terrified, Li Wen remains tight-lipped out of sheer dread for the “Painter.” Only when his “old flame,” the internationally renowned painter Ruan Wen, appears to vouch for him does he reluctantly begin to speak—though initially, he recounts only his past with Ruan Wen. It is only after Inspector He prompts him that Li Wen finally tells the story of his encounter with the “Painter”…

Of course, we later learn that Li Wen fabricated the “Painter” Wu Fusheng based on the police driver’s appearance. Yet this doesn’t diminish the believability of this “false story” when we recall it.

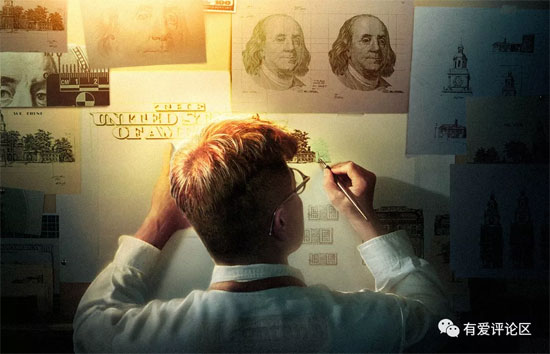

A crucial foundation for “Project Gutenberg”‘s success lies in its “professionalism,” as the dialogue states: “Anything done to perfection becomes art.”

Director Andrew Lau began researching counterfeiting crimes in 2008. Before filming Project Gutenberg, he amassed extensive case files on counterfeiting offenses. During production, he pursued “extreme authenticity”: using genuine US dollar pulp, Japanese ink, and Eastern European plate-making and printing techniques to actually produce counterfeit bills.

Typically, films tackling such criminal subjects rarely delve so deeply into recreating minutiae, preferring instead to focus more on political intrigue and hedonistic excess. Yet, the film proves that this seemingly “nitpicky” approach is far from futile. It’s hard to forget the flawless brushstrokes, the meticulous search for the right paper and oil, the ingenuity in replicating watermarks…

It’s no small feat to make such specialized content engaging without becoming tedious. A friend remarked that the counterfeiting sequences reminded him of the meth-cooking scenes in “Breaking Bad.” I suppose this is what “meticulousness in every detail” truly means.

Beyond portraying Wu Fusheng’s extraordinary skills as a “painter” in counterfeiting and trafficking, Li Wen must also cover up multiple murders he committed. Thus, the refined and elegant “painter” is simultaneously a ruthless killer.

Action sequences are another highlight of “Project Gutenberg,” primarily serving to flesh out character development. Of course, their role in delivering sensory thrills—especially that nostalgic “feel-good” boost—cannot be overlooked. After all, in Andrew Lau’s eyes, “no actor looks better holding a gun than him (Chow Yun-fat),” a sentiment shared by many viewers.

But these action sequences are restrained—Chow Wai-keung didn’t amp up the action just because Chow Yun-fat joined the cast. Throughout the entire film, there are only a handful of scenes filled with tension and gunfire…

I greatly appreciate this restraint in knowing when to stop. The decision to cut the scene where Chow lit his cigarette with a banknote is particularly admirable. While capitalizing on nostalgia yields immediate benefits, it can easily overshadow the core narrative if mishandled. Project Gutenberg masterfully navigates this balance.

In truth, Li Wen’s portrayal of “The Painter” contains numerous inconsistencies and contradictions: for instance, he declares that “a man who abandons love can’t do anything well,” only to immediately claim he’s one of the rare individuals who don’t need love. He’s presented as the last artist to join the gang, yet seems inseparable from “The Painter” at all times. And during the hotel massacre, “The Painter” clearly suffers a fatal wound, only to later spring back to life and start eliminating witnesses with vigor.

Rather than being a fabricated persona, “The Painter” Wu Fusheng is more accurately Li Wen’s alter ego.

This explains why Li Wen’s disjointed narrative remains compelling: his displayed cowardice, terror, and timidity are genuine, while the arrogance, cruelty, and hubris he conceals are equally real. Li Wen craved and needed a “Painter” to tell him “those who see only black and white are forever losers”—until he himself became the “Painter.”

By this point in the deception, “Project Gutenberg” had achieved remarkable technical mastery, though its “soul” remained incomplete… The gaps were filled by the truths of Li Wen, Ruan Wen, and Xiuqing. Not only that, but these truths elevated the film to a higher level.

During his “truth or dare” confession, Li Wen spun two lies. One was fabricating the non-existent “painter” Wu Fusheng, which made him a relatively minor accomplice. The other was fabricating his relationship with Ruan Wen. This lie seemed insignificant and inconspicuous, yet it was the more crucial one—it made people believe Li Wen’s motive and reason for “going astray,” and it made people believe the reasons and obsessive entanglement that inevitably drew Ruan Wen into it.

Yet this Ruan Wen was actually Xiuqing, one of his subordinates, disguised through plastic surgery.

The “painter” seeking revenge against the Thai general in a shootout was likely embellished by Li Wen (perhaps just a routine case of criminals turning on each other), but Li Wen risking his life to save the severely burned Xiuqing was undeniably true… Stripping away the functional layers of the entire affair, what remains is nothing but raw, bloody illusions/truths.

Li Wen saved Xiuqing’s life not only because she was also a counterfeiting expert, but more importantly—most importantly—because her figure and posture reminded him of the Ruan Wen he longed for day and night. She happened to be burned, and he held the power over her life and death—Xiuqing was precisely the highest-grade “canvas” Li Wen had found. If counterfeit money could be as useful as real money, then what difference was there between a fake person and a real one?

To Li Wen, the “Painter” was not merely the guide who steered him toward crime, but also the hypnotist who constantly whispered that truth and falsehood were irrelevant.

The timid, truth-seeking Li Wen was his true nature, and he willingly allowed the “Painter” to possess his mind and body.

“How can a man live his whole life without lying to the woman he loves?” Brainwashed by his own words, Li Wen deceived Xiuqing—and deceived himself… He and Ruan Wen had merely been neighbors for a time; she didn’t even know his real name. This was a one-sided love that never began, yet Li Wen could recount it with such vivid detail it seemed more real than reality itself. How many times had he mentally replayed and simulated it?

Li Wen was undeniably a genius at fabrication—counterfeit money, fabricated lives, fabricated love. After all, “as long as we try our hardest to act/pretend/love with genuine passion, isn’t that enough?”

But for Xiuqing, forced into the role of Ruan Wen’s stand-in, it felt unfair and unbearable.

Fairness doesn’t exist in this world, yet people will always chase it—and that’s precisely why cracks appeared in the counterfeit gang, why Xiuqing became the stumbling block that tripped Li Wen up, and why “Project Gutenberg” ended in such a bleak yet romantic way.

Beyond that, the spot-on performances by actors like Aaron Kwok and Chow Yun-fat—and other strengths—needn’t be elaborated here… What deserves the most praise this time is director and screenwriter Andrew Chong.

His rigorous self-discipline (nearly a decade of preparation), exacting standards for the script (barely altered after filming began), and profound artistic insight (noticing that many counterfeiters had artistic backgrounds, creating a resonance)… These elements intertwined to forge “Project Gutenberg.”

Creators who approach their work with such patience, dedication, and sincerity are always welcome among us audiences.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Project Gutenberg 無雙 2018 Film Review: I am my own god.