Film Name:黑鏡:潘達斯奈基 / Black Mirror: Bandersnatch

First off, my apologies—I’ve been swamped lately, so this article is arriving a fortnight late…

Given the delay and the fact that “Black Mirror: Bandersnatch” has already cooled off considerably, with many keen viewers having already explored its various modes and dissected its Easter eggs, I’ll skip those details and just share some unfiltered thoughts.

To borrow a phrase from my Season 4 review: “Black Mirror” ostensibly reflects on how contemporary technological achievements reshape humanity, society, politics, morality, and public order. Yet its core theme is the invasion of media itself—for technology is merely the visible vehicle, serves as a tool to achieve the goal of “spectatorship,” focusing all desires driven by the “medium.” More specifically, the “black mirror” refers to screens. Wherever human senses exist, there are hearts waiting to be connected, bought, and controlled.

Thus, despite “Bandersnatch” presenting a retro-themed vignette set in 1984, its core concept and essence remain quintessentially “Black Mirror”—it uses interactivity to briefly make viewers believe they are “gods determining the plot’s course,” only to shatter that illusion with outcomes that are largely similar or even converge toward the same end, reminding them, “You remain a slave to the screen.”

The reality is, audiences didn’t buy into this installment. Its media ratings and viewer reception hit a new low for the Black Mirror series.

The reason lies not in Bandersnatch’s lack of authenticity in theme or spirit, but in its execution—form overwhelming substance. Once the (possible) novelty wore off, viewers quickly succumbed to fatigue from repetitive and convoluted plot loops. Even if some takeaway emerged, it felt hollow after all empathy had been stripped away, lacking any real weight.

What exactly did Bandersnatch tell us?

In 1984, Stephen, raised in a single-parent household, is inspired by his mother’s posthumous book “Bandersnatch” to create a video game where players can choose their own story paths.

The subsequent narrative unfolds around the game’s development process and its consequences, intertwined with Stephen’s psychological struggles.

The standout feature of “Bandersnatch” is its interactive mode, allowing viewers to control the plot’s direction using a mouse, touchscreen, or remote control. Different choices lead to distinct content and endings.

This TV movie lacks a progress bar entirely. For the optimal viewing experience, viewers must stream it directly on Netflix’s website—downloading it is pointless. The full footage spans over five hours, yet completing a (relatively) comprehensive playthrough takes just an hour and a half at most. No wonder subtitle groups threw in the towel immediately after the release of pirated copies…

I was fortunate enough to attend the “Black Mirror” New Year’s event and experience the ‘authentic’ version of “Bandersnatch.” But once you actually watch it, you realize the so-called “interactivity” is just a cleverly disguised gimmick.

The choices in the film broadly fall into two categories:

One type is “pseudo-choices” that have no real impact on the subsequent plot, no matter what you select. Examples include the first choice about which cereal to eat, followed by decisions like what song to listen to or which record to buy.

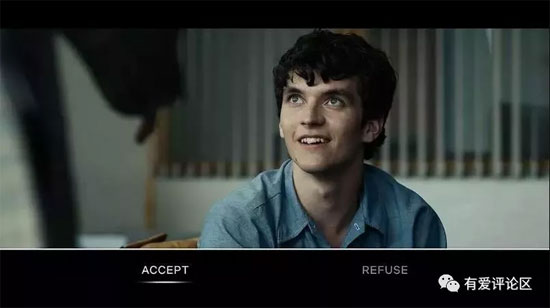

The other are “real choices” that genuinely trigger different storylines. Take Stephen’s first critical decision: whether to accept Tucker’s offer to stay at the company and develop the game. Choosing ‘accept’ leads to the film’s quickest “Dead End,” immediately cutting to the scene where “the game receives poor reviews, and Stephen resolves to make a different choice.” Only by selecting “decline” and letting Stephen go home to develop the game can you unlock the main storylines that follow.

By now, both viewers and non-viewers alike should grasp the underlying mechanism: “Bandersnatch” ostensibly grants audiences significant autonomy to steer the narrative, yet invisible strings covertly guide them toward predetermined paths. Not every divergent choice leads to radically distinct storylines.

Should viewers stubbornly persist, the film will “independently” make decisions for them.

For instance, during Stephen’s therapy session with Dr. Haynes, when asked about his mother, we chose “Talk about it” on the first watch. Yet on the second viewing, we repeatedly selected “Refuse to discuss” his mother. Still, the subsequent plot forces Stephen to open up—because without this exchange, the crucial childhood memory sequence couldn’t be triggered, resulting in a narrative disconnect.

This part is still relatively subtle… In contrast, Colin’s choice to let Stephen decide whether to take the “big picture” potion is downright blatant—even if you refuse, Colin will slip it into Stephen’s coffee anyway. Your choice makes no difference whatsoever. These seemingly pivotal moments are essentially “pseudo-choices.”

Of course, this realization only emerges after multiple viewings or repeatedly making the same “wrong choice”… During the first watch, there are indeed plenty of moments designed to keep viewers “engaged and entertained.”

The most iconic example is when Stephen realizes “someone is manipulating his choices.”

“Bandersnatch” peppers this segment with playful jokes and clever tricks, satisfying viewers’ craving for control: trivial choices like whether Stephen should pull his ear or bite his nails are designed to spark knowing smiles when he later references these minor details.

This “deep interaction” with characters peaks when viewers give Stephen an “omen”: you can choose to tell him ‘Netflix’ or the “game fork” symbol.

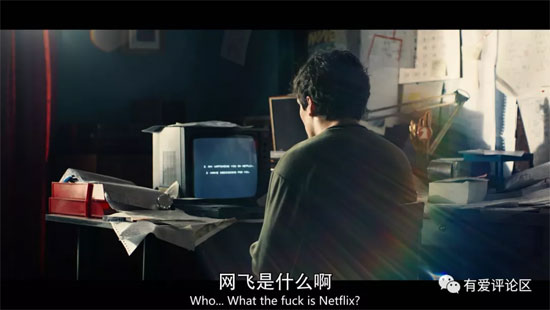

Many viewers likely succumb to a slightly twisted sense of humor by choosing Netflix, and “Bandersnatch” then feeds into this desire for chaos by unleashing even more absurd plot twists—

When Stephen’s father takes him to therapy, Dr. Haynes, upon hearing the truth, actively tempts Stephen (the viewer) into making even more jarring choices: Since we’re here for entertainment, why not stage some more explosive action? Stephen would then spill coffee, and Dr. Haynes would pull out two batons…

After that, viewers could even make Stephen fight Dr. Haynes, or even kick his father in the balls…

However, this indulgence in letting the audience “run wild” has its limits. If we prevent Stephen and Haynes from fighting and instead have them jump out the window, the scene would immediately cut to the set, informing the actors they can’t jump—”that’s not what the script says”—and instantly enter a “Dead End.” Even if the violent path is chosen, the same outcome awaits shortly after.

Thus, at this pivotal juncture, the audience must select the branching marker to truly advance the plot.

The more branching paths the audience takes and the more divergent choices they make, the more they realize their “control” isn’t as strong as it seems. While the film does offer several endings, it falls far short of reaching an “Nth power” level.

Stephen will inevitably kill his father and face the journey of burying the body. Only when the story reaches this point do viewers realize their actual choices are truly limited.

Even if some viewers stubbornly persist in pursuing a particular path to its bitter end, “Bandersnatch” will simply roll back to a previous critical juncture, forcing them to choose again.

Among the film’s prepared endings, most conclude with Stephen’s arrest and imprisonment, where he watches TV as game reviewer Robin gives “Bandersnatch” a scathing review. Like the audience, Stephen can only turn back again and again, carving another fork symbol on his cell wall, yearning to make different choices before the plot loops once more…

If you’ve reached this point, it means you’ve seen at least 50-60%, or even 70-80%, of Bandersnatch’s endings—a worthwhile journey indeed. Yet conversely, the fatigue of repetition will swiftly pull you out of the awe of realizing the film’s “ingenuity.”

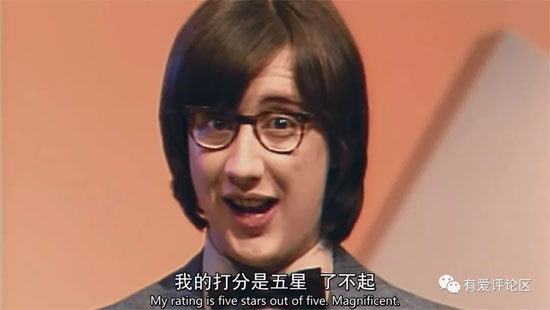

If forced to pick a best ending for “Bandersnatch,” the most “Black Mirror”-esque conclusion in my view is when Stephen violently dismembers his father, successfully completes the game, and then confidently shares his new revelation with Dr. Haynes:

“Now I see it clearly… I was trying to give players too many choices before. So I started over, stripped away a lot. Now they only have the illusion of free will, but really… I decide the ending.”

Stephen acknowledged with a slightly eerie smile that this was a “happy ending” game. The camera cut to a room plastered with design sketches, where his father’s head sat on a cabinet like a decorative ornament, the bloodstains still wet…

This scene delivered the message through actual dialogue: You think you’re making choices for me, but in reality, I’m the one choosing for you.

In fact, this is the only ending in the entire Bandersnatch game that receives a perfect five-star rating. It’s truly chilling when you think about it…

Yet this is merely an alternate ending (and not the final one). When the story shifts to the present day and Netflix employees attempt to reboot Bandersnatch, the plot inevitably returns to the pivotal choices.

So, do you like this work?

Why do we love “Black Mirror”?

Before pondering that question, let’s first discuss why we love the “Black Mirror” series—there are likely many answers, but I’ll share a few common reasons based on my own experience.

The helplessness of being swept up by “consumerism” and “entertainment to death” yet unable to resist.

Take my favorite episode, S1E2 “The 15 Million Dollar Man.” The protagonist, Madsen, intended to use his own blood to denounce the fucked-up reality and society in front of everyone…

Yet his rage and despair were easily dismissed by the judges as mere “performance.” Madsen was then manipulated and bribed, moving from a cramped little room to a larger one… What’s even more disheartening is that after witnessing such stories, few of us can muster the strength to make real change beyond initial shock.

When the massive twist hits, we shiver and tremble, pierced by a reality that is absurd yet undeniably true.

Take the highly popular S2E2 “White Bear” as a prime example. After enduring several bizarre minutes, we finally grasp that the protagonist, Skylan, is the defendant subjected to countless public punishments within the “White Bear Justice Park.”

The desire for criminals to “get what they deserve” is a common sentiment. Precisely because people believe they stand on the side of “justice,” this platform exists—a place where criminals face eternal damnation and the public experiences retribution. Yet this ideology and practice of violence in the name of justice persists, never ceasing.

They become utterly lost in an illusion where fake becomes real, trapped in a drunken, dreamlike state.

S3E4 “San Junipero” is a particularly deceptive episode. Many viewers might even find themselves drawn to the idea of transcending life and death after watching it, rather than feeling uneasy.

Despite the show hinting that “immortality” leads to endless emptiness, this doesn’t stop Yorkshire and Carrie from dancing wildly in TCKR’s database… As for the underlying reality questions? Does anyone truly care anymore?

Countless possibilities were designed, yet no definitive conclusion emerged.

S4E4 “Hang the DJ” invites multiple interpretations, but its most brilliant aspect remains this: even after two strangers fall in love a thousand times through the “ultimate dating app,” achieving a staggering 99.8% match rate, they remain fundamentally strangers.

By all accounts, the relationship between the male and female leads should have unfolded naturally. Yet even as the final scene plays out with “Hang the DJ” playing on repeat, we still don’t know whether Amy walked toward Frank or turned and walked away.

Great works—especially those like “Black Mirror”—often pose sharp questions without offering definitive answers, leaving room for viewers to ponder, debate, and interpret for themselves.

Judging “Bandersnatch” by this “formula,” it actually deserves high marks, as it possesses nearly all the strengths that have defined “Black Mirror” in the past.

The core theme of “Bandersnatch” is “self-awareness, control versus counter-control, and divergent destinies shaped by different choices.”

On one hand, it repeatedly hints at the “irreversibility” of fate through early narrative cues. Yet after triggering Colin’s pivotal storyline, it subverts this implication—using a “let me be honest with you” tone to suggest fate is alterable, implying everything unfolding is part of a grand conspiracy.

To convey the sensation of “seemingly different yet strangely familiar,” the film embeds numerous clever references: When Stephen returns to Tuck Corporation, he immediately mentions the game name ‘Downfall’ and the “buffer error” previously spoken by Colin. Similarly, after Colin’s fall to death, when Stephen re-enters the storyline, Colin greets him with the familiarity of someone who’s been there before.

Additionally, “Bandersnatch” is packed with Easter eggs: the murder weapon ‘Metalhead’ in S4E5 is one of Tuck Corporation’s signature games; psychologist Haynes shares the same name as the Black Museum curator in S4E6; the fork sign Stephen sees bears the “White Bear” logo; Netflix even created the game “Nohzdyve” and a website accessible via the final audio code…

Twists, scares, chills, confusion, intricate details—and multiple endings.

Beyond the previously mentioned “five-star review” conclusion, my favorite is the ending where Stephen travels back in time to retrieve the rabbit, resulting in young Stephen and his mother dying in an accident, while adult Stephen perishes in the therapist’s office.

Unlike the previous ending that gripped viewers’ throats with a sinister chuckle, this conclusion further highlights the imprint and impact of Stephen’s childhood trauma, cleverly masking the environment’s relentless pressure with tenderness and sorrow.

Yet this is precisely where Bandersnatch stumbles: its paths and endings remain overwhelmingly numerous.

If it truly offered “2 to the Nth power” variations, that might be acceptable. The reality is it barely exceeds 300 minutes… After believing they’ve reached a satisfying conclusion, viewers find no clear stopping point and are often compelled to follow prompts forward. The desire to explore more divergent storylines drives them to make further choices. Expecting to complete the entire experience in an hour and a half without repetition is simply impossible—the only way to avoid this complexity is to exit the viewing altogether.

Thus, the most ingenious selling point of “Bandersnatch” also became its fatal flaw: under the relentless barrage of plot twists, viewers gradually grasped the story’s intended message, causing their emotional investment to steadily fade… The film never truly attempts to captivate its audience. By the time it proclaims “You are all my slaves,” few remain trapped within that open cage—audiences typically cheer only when they’re unknowingly imprisoned.

It must be said that the “interactive mode” represents Netflix’s bold experiment following “Black Mirror,” and its innovative spirit deserves recognition… But they also demonstrated to everyone that this experiment was not successful.

Interactive cinema has existed for decades, perpetually stuck in an awkward limbo of “all talk and no action.” To truly immerse users, games with stronger narrative immersion (like last year’s Detroit: Become Human) are clearly a superior choice.

Netflix’s unconventional approach backfired this time (at least it didn’t succeed), because this format simply isn’t suited for mainstream TV and film production at this stage—or perhaps ever. Learning from this lesson, the creators of “Black Mirror” have explicitly stated that future episodes won’t feature interactive formats.

Here’s hoping that the next time the spinning circle appears and the screen shatters, we’ll witness more stories beyond description.

Please specify:Anime Phone Cases » Black Mirror: Bandersnatch 黑鏡:潘達斯奈基 2018 Film Review: This time, we won’t be slaves to our screens.